I suspect that this post will make some readers angry. That’s not my intent, but it’s probably inevitable, because I want to ask some politically incorrect questions which no one seems to be willing to take on.

This year in the Pacific Fleet there have been three collisions and a grounding of combatant ships, a terrible record previously unmatched by the U.S. Navy. A quick search online will bring up several articles about the details of each incident.

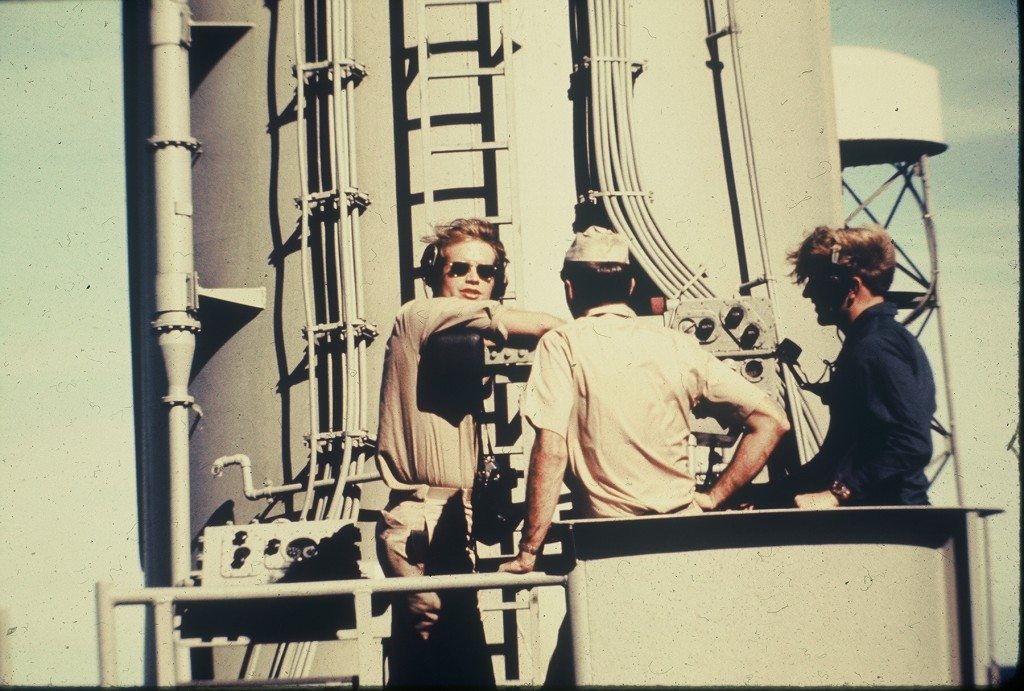

The two recent, tragic collisions at sea involving the USS Fitzgerald and the USS McCain, both modern guided  missile destroyers, have a personal resonance with me. In December, 1972 I served as one of the Officers of the Deck on the USS Wainwright, at that time a modern guided missile frigate, beginning seven months of operations in the Mediterranean. I was twenty-five years old and had been on the ship for eighteen months.

missile destroyers, have a personal resonance with me. In December, 1972 I served as one of the Officers of the Deck on the USS Wainwright, at that time a modern guided missile frigate, beginning seven months of operations in the Mediterranean. I was twenty-five years old and had been on the ship for eighteen months.

The ship of course operated 24/7, and whenever the Captain was off the bridge, either I or some other mid-twenties liberal arts major and his watch team were responsible for the safety of the ship and its 400 man crew. Onboard we had explosive ordnance, nuclear weapons, torpedoes and lots of fuel. The prospect of colliding with another ship was always possible, even in a vast ocean, and so we focused whenever the radar or our eyeballs indicated that any ship would come closer than ten miles. If any ship was projected to come closer than five miles, I had to call the captain, explain the situation, and tell him what evasive action, if any, I proposed. He would concur, or come immediately to the bridge to see for himself.

And we assumed that large tankers and container ships were probably on automatic pilot, meaning that we had to stay far out of their way.

But that December we were tasked with trying to find a Soviet cruiser coming from the Atlantic through the Strait of Gibraltar into the Med, and the Pentagon believed that a Soviet submarine would be hiding just under it. That meant that during the day we would send our helicopter out for wide area searches, but an aerial search would not work at night.

The Strait of Gibraltar is a choke-point, only nine miles wide, forcing ships of every size into very narrow lanes, similar to the conditions in the two heavily trafficked areas where the Fitzgerald and McCain were operating. As ships sailed through the strait going west-east, or vice-versa, we on the Wainwright had to traverse north and south across their lanes, and then get close enough to shine our searchlight on any ship which looked like it could be the cruiser.

Usually when one came up to the bridge to relieve the watch at midnight there would be a couple of ships showing on the surface search radar, turned out to 25 miles. In the strait, the radar looked like it had the measles, while focused in on 10 or even 5 miles. We had extra look-outs and extra men on the radar repeaters. Turning to avoid one ship might point us directly into the path of another. Not easy sailing, but we did it with rotating well-trained teams that stayed focused.

After a couple of long nights like this, we actually found the cruiser; her Soviet captain had reconfigured her deck lights to give the appearance of a civilian ship. For the next few days we played cat and mouse with our Soviet counterparts in the Western Med, pinging on their submarine, as the two Navies did regularly back in those days.

After a couple of long nights like this, we actually found the cruiser; her Soviet captain had reconfigured her deck lights to give the appearance of a civilian ship. For the next few days we played cat and mouse with our Soviet counterparts in the Western Med, pinging on their submarine, as the two Navies did regularly back in those days.

But back to the Fitzgerald and the McCain. The Navy has issued a report on the former which mainly details the incredible heroism and sacrifice of the crew after the collision. Seven sailors were killed. There is little mention in the report of how or why the collision occurred, but the ACX Crystal had the right of way, and according to www.navaltoday.com:

The navy said the collision was avoidable and both USS Fitzgerald and ACX Crystal demonstrated poor seamanship.

Within Fitzgerald, flawed watch stander teamwork and inadequate leadership contributed to the collision that claimed the lives of seven Fitzgerald sailors, injured three more, and damaged both ships.

USS Fitzgerald’s commanding officer, Cmdr. Bryce Benson was relieved due to a loss of confidence in his ability to lead. The navy added that inadequate leadership by the executive officer, Cmdr. Sean Babbitt, and command master chief, Master Chief Petty Officer Brice Baldwin, contributed to the lack of watch stander preparedness and readiness that was evident in the events leading up to the collision.

Several junior officers were relieved of their duties due to poor seamanship and flawed teamwork as bridge and combat information center watch standers. Additional administrative actions were taken against members of both watch teams.

If you look around on the internet you will see some theories about possible sinister GPS spoofing or bad communications between the two ships as causes. While anything is possible, it was a clear night, and I have to ask: what did their own eyeballs tell the watch crew? How do you miss a huge container ship, three times your size, at close range and closing?

There has not yet been an official report on the McCain, and I have no special insider information. My purpose here is not to give final answers, but to ask questions and hope that the Navy might consider them to be relevant.

So here goes. The press has been reporting that the pace of Naval operations has increased across the world, particularly in forward-deployed areas like the Pacific, while the resources to conduct these operations, both ships and people, have decreased. Meaning less or no training time, longer deployments, and generally increased fatigue.

ships and people, have decreased. Meaning less or no training time, longer deployments, and generally increased fatigue.

I get that, and it is a weighty factor, requiring mid- to long-term solutions. But I still don’t understand how increased operations lead to two deadly collisions at sea in ten weeks unless something else is going on. One could easily make the case that increased operations should lead to increased watch team readiness, given the time spent working together.

I’m going to ask: Is there anything different about the Navy today than when I was serving as an officer? Besides better ships and better technology? One answer is that the Navy and the other branches of our Armed Services have become giant experiments in progressive social engineering. Could that have anything to do with the quality, focus and activities of the men and women actually standing watch?

I don’t know. I’m asking.

Given what you know about being eighteen to twenty-five years old, would it make sense to you to put young men and women together for many months in highly dangerous and stressful situations, and command them not to think about or to care for each other? Command them to focus on the duty at hand, and not on relationships or the latest text, when their civilian peers are glued to their social media? It just seems impossible to me that there are not other agenda just below the surface with many groups on any ship—who is dating whom, who is new onboard–and is he or she available, who is jealous—which generally undermine the focus and the readiness required for complex operations.

And I ask whether this issue is relevant to all the services? The Navy may be the canary in the coalmine, because when just a few people don’t work well together on watch in the Navy, there can be very visible, expensive and deadly results which are difficult to cover up in the name of political correctness.

And I ask whether this issue is relevant to all the services? The Navy may be the canary in the coalmine, because when just a few people don’t work well together on watch in the Navy, there can be very visible, expensive and deadly results which are difficult to cover up in the name of political correctness.

I am not questioning the ability, intelligence, loyalty or patriotism of any individual straight woman, gay or lesbian serving in our Armed Forces. I am questioning the command decision to mix together this diverse group in the unique confines of a Naval combatant for months on end, and then to be surprised when feelings and hormones overcome standing orders, the task at hand, or codes of conduct.

I understand that the Navy, like the other services, really doesn’t want to touch this subject. Careers can be ruined for asking these questions. But just coming at it tangentially, here are two indicators of what may be below the surface.

First, a recent article, “The Love Boats Sail Again” in The Washington Times, indicates that 16% of women in the Navy, after they are trained for specific duties, fail to make their ships’ deployments because they become pregnant. Leaving aside the moral and relational implications, that simply means that someone else—man or woman—left behind onboard the ship must fulfill that extra duty, adding to the already increased stress noted above. Plus wasted training cost and increased medical expenses.

Second, following is an excerpt from a moving article in The Daily Press of Newport News, Virginia, “After the Fitzgerald Tragedy, Two Women Bond Over Their Sailors”, about a hero on the Fitzgerald, Gary Rehm, who gave his life so that others could live. The story centers on Jacqueline Langlais, a sailor on the Fitzgerald, who was the older Rehm’s best friend, while engaged to Dakota Rigsby (also killed in the collision), a newer sailor on the ship and another of Rehm’s friends. Let me be clear that all three of these sailors, and Rhem’s widow, Erin, are heroes. From all that I can tell, they are incredibly loving, supporting members of the frontline Navy family . I have not suffered anything like what these two women are now going through with the loss of their loved ones. I quote from the article below to describe deep and genuine relationships onboard a Navy ship which simply were not possible until recently.

“Gary was my best friend,” Langlais said, “so he brought Dakota over to my house one night and said, ‘I want to introduce you to one of my guys — my kids.'”

Because Rigsby was new to the ship, Langlais invited him to come over and hang out, if he wanted. She wasn’t looking to get romantically involved, having just gone through a breakup.

Because she wasn’t seeking a relationship, she wasn’t out to impress him. That turned out to be the charm.

“I could just be myself around him,” she said.

They started dating. They fell in love. Rigsby proposed to her one month ago.

“He was super-adorable,” she said. “He loved me for who I was. I didn’t have to change anything.”

They would talk about getting married and what they would name their first baby. It would be a girl named Mya. At night, they would go to middle part of the Fitzgerald and watch the sky.

“We would just sit there and watch the stars,” she said. “It was pitch black and the stars were so beautiful.”

With a laugh, she said whoever falls in love with her will have to deal with a lot of baggage. After all, she’s already named her first baby girl. And her second child, she’s decided, will be named Dakota Leo — Leo being Rehm’s middle name.

“It’s just hard because those are my two best friends on the ship,” she said. “I think the whole ship kind of considered us the trio. We never went anywhere without each other.”

These four individuals have loved much and lost much. It makes the terrible gashes in the side of the ship much more personal. In general, deep and loving relationships are of course good and to be encouraged. I am simply asking whether  a combat ship is the proper place for them, and whether it is inevitable that such relationships impact how people on duty work together in roles where emotion, courting, love and potential jealousy must have negative consequences.

a combat ship is the proper place for them, and whether it is inevitable that such relationships impact how people on duty work together in roles where emotion, courting, love and potential jealousy must have negative consequences.

Whatever our political philosophy might be on other subjects, may we all agree that nurturing a loving relationship for others in one’s military unit is not a mission for our Armed Forces, whose singular focus should be to defend us from terrorists and other committed aggressors?

So, I’ve asked some uncomfortable questions. I acknowledge again that my concerns may be valid, or they may be completely off base. I don’t know. Perhaps the Navy will inquire about how they impact readiness, but probably not any time soon.

If this subject interests you, please see an earlier post, and you might enjoy a novel I wrote over two decades ago, The President.

Whatever the causes—technical, training, deployments, cyberwar, or too much on the heart and mind—the Navy must figure it out soon. We cannot continue to lose great people like Rehm and Rigsby, and important ships like Fitzgerald and McCain, due to avoidable human error.

The current “screwed up” state of today’s military is the predictable outcome of all of this “social engineering” that has been forced on our military by politicians seeking votes from all possible sectors of our population. Unless this bent is reversed, more negative outcomes will be forthcoming. Other nations are laughing at us, and are saying that they don’t have to worry about any threats from the U.S., because we will destroy ourselves from within (reminiscent of the Roman Empire’s decline due to internal corruption, etc..) These policies are also a reflection of what is happening in the nations educational institutions and other sectors of our society.

In British Columbia, one of our BC Ferries hit an island travelling a route it had made many hundreds of times before on a clear night, after midnight I believe. It has been reported two were on the bridge and had been a couple, then separated. It was reported they were arguing during their time on the bridge. As you know they would have had to ignore radar warnings. Two lost their life due to this sinking. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dw3mZ3CZ2fY

The operational complications casued by the integration into the Armed Forces of people who are romantically attracted to each other are real and cannot be legislated away.

The operational implications will never disappear nor is that the goal of our society, in contrast to the racial integration of our Armed Forces that took place immediately following World War II.

Racial integration had short and medium term negative operational effects that the chain of command had to work to overcome. But over the long term doing so helped improve overall operational efficiency and contributed to the breaking down of racial barriers and the reduction of racial predujice in our country.

I think that we can all agree that eliminating racial prejudice is a worthy societal goal and that our racially integrated Armed Forces are stronger.

But it is not our goal to create a society where men and women no longer fall in love, get married and have children.

Thus, we have to admit that the operational issues created by men and women serving together will always be there.

The first women graduated from the military academies in 1980. With separate barracks rooms, bathrooms and gym facilities the military has not forced men and women to literally sleep together or have other intimate contact. There was and is extensive training on proper and improper relationships between peers and between leaders and their subordinates.

Almost 30 years of statistics show that the operational issues of pregancy, sexual harrassment and improper relationships will never go away. We have the same issues in civilian government service and in business.

But to suggest that we turn back the clock and roll back or fully segregate the involvement of women in our military is not a realistic proposition – it would go against widely held values of our society. And frankly, if Navy ships had begun regularly colliding with other ships soon after women came aboard then I think we might find some causation. But that did not happen.

What about allowing homosexuals to openly serve? Operationally, what is different here is that for the first time the military IS forcing people who are attracted to other people to sleep with each other and share showers and bathrooms. Is this not fundamentally a different operational challenge that cannot be physically managed in the same way?

The same situation is created when you put women into the infantry – where they sleep and perform personal hygiene in the same foxhole with a man where there is a natural mutual attraction.

Are we not under estimating the operational challenges that these new changes make? – and putting our young people into even more difficult emotional situations? Frankly I believe the political correctness of people who never put themselves in such a situation creates another major emotional challenge to our young people, who are exposed to far more mind boggling moral choices than we were as teenagers.

I do believe that we must not forget that serving in an effective military involves giving up some freedom and individual rights. Discipline and hard training must be part and parcial of serving and it is only through them that operational challenges are overcome and ships avoid running into each other.

West Point grad & Desert Storm scout platoon leader

I did read the President, and recommended it to friends as I thought it is very relevant to things happening today. As soon as these “accident” started happening I thought about some of the questions you are asking. I have no answers, but I hope you will be able to find some.

Parker, you raise valid questions here. If you were to expose the social engineering at our military academies today, you might get closer to the answers. The distractions from military training and preparedness for officers are striking compared to the post war years when leadership at these academies was focused, disciplined, experienced and hardened by the realities of war. We may be graduating smart, technically trained cadets today but, my question is “would you get into a foxhole” with one of them?

Well stated, Parker… pointing out one (the Navy’s) experiment among the several going on in our military. I served as a USAF pilot during our country’s Vietnam “conflict”, and believe that the discipline and focus you describe for duty personnel is absolutely essential for readiness, battle effectiveness and certainly, survival. It is a shame that our society today permits (even demands) these shameless experiments that put the brave men and women of our military services in danger along with the entire nation.

Excellent letter… A lot to think about here…. ?